Maximum Size

30 cm

(12 inches) across

Depth

100–4,100m

(330–13,500 feet)

Habitat

Seafloor

including muddy seafloor and rocky outcroppings

Diet

Plankton

Range

North Pacific Ocean

Alaska to California, also occurs in the northwestern Pacific Ocean

About

This is not your average anemone.

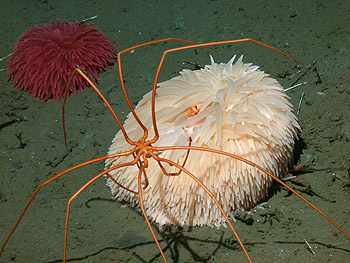

While most sea anemones have a stalked body with a crown of tentacles, the pom-pom anemone (Liponema brevicorne) is a tuft of tentacles. Their shape can vary considerably—sometimes deflated and stringy, sometimes round and puffy, and sometimes bulky and barreled. Liponema comes in many colors too, from brilliant blush and pale white to vibrant pink and even regal purple.

Liponema is not content to stay still. Using their muscles, they can contort their body into a barrel-like shape and roll across the seafloor. “Blown” by the currents, the anemone moves along the mud like a tumbleweed in the desert. We think this behavior allows Liponema to seek out new environments where food may be more abundant.

Once they find the right spot, they stretch out their tentacles in all directions. Like other anemones, those tentacles are covered in venomous stinging cells that catch crustaceans and other tiny plankton passing by in the current.

The pom-pom anemone is an important part of seafloor communities. Much of the deep seafloor is a flat muddy expanse. An inflated anemone provides habitat and shelter for shrimp, amphipods, and even fishes. We have also learned that Liponema may be an important source of food for giant sea spiders (Colossendeis sp.). The sea spiders suck material from the anemone’s tentacles. Luckily for the anemone, this does not appear to cause much harm. In fact, the pom-pom anemone can shed tentacles, providing a takeaway treat for a dine-and-dash sea spider.

Predator and prey, host and hitchhiker—life in the deep sea is a mosaic of complex interactions that we are just beginning to understand. However, we do know that human actions like fishing, pollution, and climate change are already affecting deep-sea animals and environments. Our research provides important information so resource managers can enact protections for animals and habitats deep beneath the ocean’s surface.

Publications

Braby, C.E., V.B. Pearse, B.A. Bain, and R.C. Vrijenhoek. 2009. Pycnogonid-cnidarian trophic interactions in the deep Monterey Submarine Canyon. Invertebrate Biology, 128: 359–363. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7410.2009.00176.x

Lundsten, L., K.L. Schlining, K. Frasier, S.B. Johnson, L. Kuhnz, J. Harvey, G. Clague, and R.C. Vrijenhoek. 2010. Time-series analysis of six whale-fall communities in Monterey Canyon, California, USA. Deep-Sea Research Part I, 57: 1573–1584. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2010.09.003